Whilst interviewing Mike Wade at his studio, a parcel arrives. ‘That’s Renaldo’s kit’, he says casually. His actual kit? ‘Oh, yes’ replies Mike as if receiving the clothes of the rich and famous was an everyday occurrence, which of course it is, if you are one of the world’s leading waxwork sculptors.

Whilst interviewing Mike Wade at his studio, a parcel arrives. ‘That’s Renaldo’s kit’, he says casually. His actual kit? ‘Oh, yes’ replies Mike as if receiving the clothes of the rich and famous was an everyday occurrence, which of course it is, if you are one of the world’s leading waxwork sculptors.

Mike has a fascinating story about how he started out and how his company has come to be recognised for it’s exceptional quality and attention to detail. ‘I left school at 16’, he says, ‘with very little clue about what I wanted to do’. He fell in with an eccentric Irish builder and started to work for him renovating pubs. ‘This was back in 1983 and this guy was really at the forefront of creating the theme pub and the gastro pub’. His big idea was The Pie Factory Pub in Tipton, where Mike ended up sculpting a full size cow for the interior. ‘That wasn’t the end of it though’, says Mike, ‘he also wanted a huge pig’s head, oversized pies, sides of beef and a mincing machine. It wasn’t a pub for vegetarians’.

He loved doing it, but with no experience, taught himself as he went along, with the help of some well thumbed library books (no internet in those days). His then girlfriend saw an advert for model makers at Madame Tussauds and he applied as a bit of joke. “I got an interview’, he says, ‘but I didn’t hear anything back for three months. Eventually, I thought I would give them a ring and they said “Where are you? Come and start now”.’

So, Mike made his way to London and the famous studio of Madame Tussauds. ‘It was so intimidating’, he recalls, ‘they asked me if I had brought my tools, which of course I hadn’t, because I didn’t own any’. It was a brilliant time to join the company, however, as they had decided to take on some new blood, as many of the old boys were nearing retirement age. ‘People often think I must have been very good to get the job, but really I think it was because I knew so little. They were looking for people to train up in their particular way of working’.

Of course, the Madame Tussuads way was very traditional. ‘It was a slow and meticulous process’, says Mike, ‘using ways of working that had remained the same for hundreds of years’. It would take fifteen separate pieces to make a head for example. Mike stayed with the company for thirteen years—‘it was an amazing apprenticeship, where I really learnt my trade’. The blasé approach to wardrobe might also have been fostered here.

‘We had a huge wardrobe at Madame Tussuads’ says Mike, ‘including clothes bequeathed to us from famous murderers for the Chamber of Horrors. It wasn’t unusual for staff to borrow clothes from the wardrobe department, especially if we had weddings or formal events to attend. I went to a wedding once wearing President Mitterand’s shoes’. Other ‘borrows’ weren’t quite so benign. ‘I was renovating a tiny house in Notting Hill at the time’, recalls Mike, ‘we had no bathroom, so I borrowed an old tin bath that I was told had come from Warwick Castle. After several months of use, I came across the Warwick Castle brochure with a photo of a tin bath in it that looked nothing like the one I was using. A little further research revealed that the bath I had been using came from John Chritsie’s house (10 Rillington Place), the scene of multiple gruesome murders in the 1940s and 50s. I took it straight back to the storeroom’.

After Mike’s long stint at Madame Tussauds, he felt the company was changing. ‘It was becoming more and more corporate and losing some of its character’, so he made the change and went freelance. His first jobs were strange, to say the least. ‘My very first commission was an effigy of Father George Preca that was taken to the Vatican to be blessed by Pope John Paul for the beatification’. He also worked for an old funeral directors based in Holborn making death masks ‘mainly for Italian aristocrats’.

However, he also was commissioned to make the death mask of Anthony Burgess. ‘His widow lived in Bakers Street, so I decided to take it to her personally’, says Mike. ‘She was obviously grieving and traumatised by her loss. When she saw the mask she absolutely hated it. “He looks so peaceful” she said “whereas in life he was so animated”.’ Mike took it away and didn’t accept payment for it. He recently donated it to the Anthony Burgess Foundation.

Since then, Mike has gone from strength to strength with his business, currently employing a team of freelancers to help realise his commissions. His portfolio is extensive, making figures as diverse as Beyonce through to Mother Theresa. Work shows no sign of slowing down and he has a full order book. ‘Much of my work goes abroad’, he says, ‘I work with a lot of small family owned waxwork museums on the continent, which is lovely as it feels like the old days at Madame Tussauds’. He also produces work for larger museums (Renaldo is off to a museum in Portugal) and public and private collections.

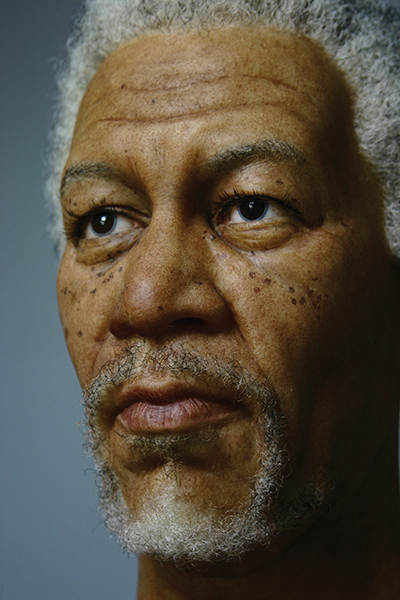

The work is still produced slowly—it takes three months just to make the head—and a further month to put the hair in, strand by strand. Mike has dressmakers to recreate outfits with painstaking attention to detail, as well as dental technicians to recreate the teeth. However, it is the eyes that are the most incredible and lifelike. Made by a specialist (Mike is understandably reluctant to reveal his sources) they are superbly made and instantly bring the face to life. ‘The eyes are the hardest’, he says, ‘not just the actual eyeball, but the exact way it sits in the socket and the surrounding eye area’. The eyes Mike has made are so realistic they are even the right shape, complete with corneal lump.

Mike’s studio is full to bursting with work in progress and it makes fascinating browsing. By his own admission, waxworking is an unusual profession and one that has more than a passing relationship with the macabre. ‘As a child I was fascinated by all the old classic horror films’ he says, ‘Madame Tussaud herself started out by making waxworks of corpses’. It is a fascinating tradition that is being kept alive right here in Dorset by the talented Mr Wade.

For more visit www.wadewaxworks.com.