Deciding what the world may see of Guantánamo Bay is an uncertain process. Over the years, representing the detainees with my colleagues at the charity Reprieve, I have indulged in a little light entertainment testing the limits of the censors’ paranoia. For example, Jack and the Bean Stalk got banned—perhaps because detainees might escape, using a magic bean. Sometimes the censors are more depressingly predictable: with art that portrays torture.

Eighty of my clients are free, but there are two fine artists among the forty men who remain there, seventeen years after it was opened. Under President Donald Trump some of their pictures have no more chance of release than they do. When Ahmed Rabbani portrayed himself being subjected to strappado—an age-old torture once employed by the Spanish Inquisition – the censors’ stamp came down hard. Admitting your international war crimes is, of course, a threat to national security. During my visits to the prison, I have seen Ahmed’s torture pictures, as well as Khalid Qassim’s, and I wish you could too. You never will. However, the censors did allow my detailed description of them out. For example, “a dark haired man is in a twenty-foot pit, a square of neon light above him … his wrists are shackled to a bar … he is forever on tiptoes. And there he stays for days on end.”

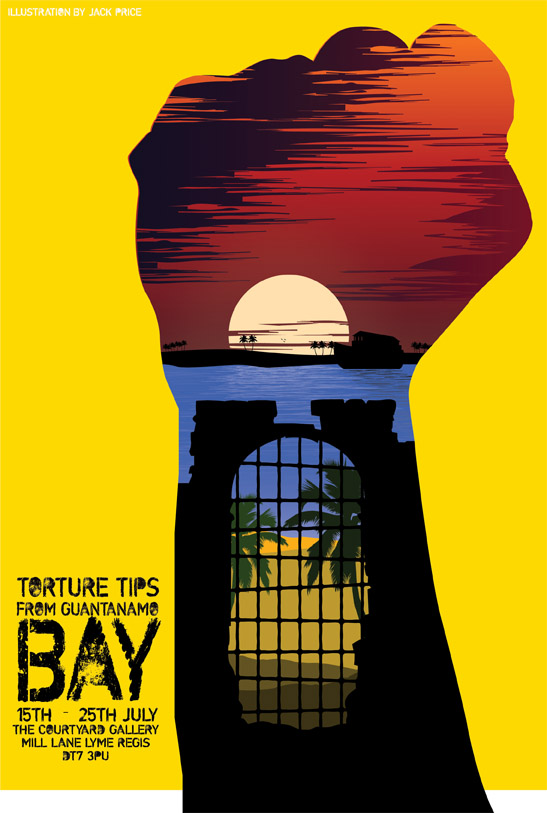

Curated by student Ruby Copplestone, Torture Tips from Guantánamo Bay brings professionals from Axminster to Australia together with artists from Woodroffe School to reinterpret Ahmed’s and Khalid’s art—liberate it, if you will—so visitors to the Town Mill Courtyard Gallery may see that which is forbidden. Later in the month, the project will link arms with Shire Hall in Dorchester, where Royal Academy artist Bob & Roberta Smith is leading a programme on the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Some parallels are obvious: the agricultural labourers, demanding fair treatment, were accused of swearing a secret oath to an evil union assemblage; they were rendered 10,000 miles to Australia for their sins. Almost two centuries later, Ahmed and Khalid were accused of swearing an oath to another hated group (al Qaida), of which they were likewise innocent. They were rendered in turn round the globe from Karachi to Guantánamo Bay. It is here that the parallel ends: after two years, public outrage prompted the government to pardon the Tolpuddle Six. Ahmed and Khalid have never enjoyed even the inequitable Shire Hall trial permitted in 1834, and they remain in their Cuban prison cells after 17 years.

Ruby Copplestone shines a light on their plight. I will be one of several ‘experts’ privileged to give a series of talks during the ten days of Torture Tips from Guantánamo Bay—from July 15-25. I hope you will join us.