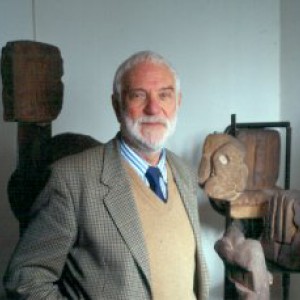

A pivotal figure in the development of sculpture in the 20th century, Sir Anthony Caro is commonly referred to as Britain’s greatest living sculptor. Born in Surrey in 1924 he is celebrating his 80th birthday this year with an exhibition at Kenwood House in London from July 1 – 25.

After studying sculpture at the Royal Academy Schools in London, he worked as an assistant to Henry Moore and came to public attention when he exhibited large abstract sculptures brightly painted and standing directly on the ground.

His innovative work has helped elevate abstract sculpture to a level of acceptability that has paved the way for many artists to focus on their own vision, rather than follow established pattern. We asked him if he felt the ‘figurative versus abstract’ debate in sculpture, could today be put to rest. “I don’t think that it is a valid debate,” he says. “I think the debate is between good art and bad, not between non-figurative and figurative. And I think that there is good art in both and bad art in both. I have found that I can span it, I don’t mind whether I am working figuratively or abstractly. I don’t want to know that difference.”

Already an enormous influence on the work of younger artists, his use of materials was very industrial in the 60s and 70s. Speaking of that early work he says, “It certainly was not pastoral and it still is not. But I use any material that is useful, easy to work with and does what I want it to. And it happened that steel did do that. So, in a sense, my work was urban rather than pastoral, but I would say there wasn’t so much materials then. I still do the same thing. I still go to scrap yards. There is a wonderful scrapyard near Winchester. I go down to the South of France and I make clay sculptures there.”

As patron of Dorset Art Weeks he offers a powerful inspiration to any artist hoping to develop their work to new levels of recognition. We asked how difficult might it be for artists living outside an urban environment to be successful. “I don’t think it is very easy for a Jackson Pollock to come out of West Dorset necessarily, because I think you have got to have some contact with other artists really. On the other hand look at St Ives and how that has become a centre. So it is possible for a place to become a centre. But I think total isolation is not terribly healthy because you don’t get quite enough input.

“Personally I am a believer in communication and everybody talking to each other and saying, ‘what do you think about this’ and ‘I’ve got this idea’ and ‘let’s see what you’ve done last week’. I think that is very fruitful but I don’t know how much that happens in London even. I think it is less likely if you are shut away.

“But on the other hand there are some very good artists in Dorset and I get surprised when I go around and see some studios and I come away and think, ‘my God that was good and I didn’t even know it existed.’ So that can happen too. There are no rules, are there?”

His view on collaboration is borne out in his work on the Millennium Bridge. Described as a blade of light over the Thames, the bridge was designed jointly by Arup, Foster and Partners and Sir Anthony and is a piece of landmark engineering and design.

Although he studied engineering – did he ever dream that one day he would help build a bridge over the Thames? “No. Never. If I had become an engineer it would have been bridges that I would have liked to do or that sort of thing. It didn’t work out in that sort of sense at all because we had a very good engineer indeed on the bridge and we had a very good architect, so I never had to worry about that side of things at all. The worst worry on the bridge was the damned planning and trying to make it happen. That was the difficulty. There were three years of talk before you could start building. This is why I am so glad I am not an architect, I think they have a tough time – keeping your vision.

“I do think it is a beautiful bridge. Norman Foster managed to get that thing through all the hurdles and in the end of it he has got something very beautiful. It worked out very well.”

At 80 Sir Anthony shows no signs of tiring. He doesn’t feel the need to go through the tiresome processes involved in public building again. Speaking of the bridge he says, “The sculptural aspect of that was cut back a lot, although the bridge itself is ok, but the stuff on the Southside was changed a great deal and the stuff on the north side should have gone right up to St Paul’s. It was cut back too much and I don’t want to go into the public realm very much.”

However, that doesn’t mean he wouldn’t consider other collaborations. If the opportunity is right it should be considered, he says. “Somebody came to see me the other day and said ‘I know a jeweller in Madrid. Have you ever thought of making any jewellery,’ and I hadn’t. I am not particularly interested but I might do it, I might just go and see. That’s the sort of thing that comes up. Or somebody says have you ever worked in paper three-dimensionally and I say ‘No. Let’s try’. I have worked in paper three-dimensionally actually, but I mean things come up like that and you don’t miss opportunities, you try and follow up on them, I think.”

And is there such a collaboration planned at the moment? “I have got a sort of scheme afoot, which we might follow up. But I would like it to be more trouble-free than the bridge. We haven’t got very far. I have made a sculpture, which Norman (Foster) says ‘My God it is a building, we’ve got to make that into a building’. Maybe we’ll do that.”

Sir Anthony’s exhibition at Kenwood House in July will consist of 16 new works and will be accompanied by a new book by Julius Bryant, with photographs by John Riddy. A major retrospective planned for Tate Britain in London in January will include some of the ground-breaking sculptures that made his career.