With an exhibition space at Bridport Arts Centre, a charity and a Sunday Times essay competition named after him, British broadcaster, author and naturalist Kenneth Alsop’s impact on conservation and literature is well highlighted. In this year’s Kenneth Alsop Memorial Talk at Bridport Literary Festival James Crowden looks forward to speaking to Mark Cocker.

This year the speaker is Mark Cocker, author of Claxton: Field notes from a small Planet and Crow Country which received excellent reviews from Richard Mabey – ‘Luminously beautiful and dartingly intelligent’ as well as a ‘thumbs up’ from Horatio Clare and Melissa Harrison. Mark Cocker is a bird man and with Richard Mabey he co-produced a learned tome called Birds Britannica. This was followed by Birds and People which with 600 pages weighs in at almost 3kg. This covers all manner of interactions between people and birds in 82 different countries, even Kazakh eagle hunters. Mark’s other writing includes: A Tiger in the Sand, Birders and the lives of eccentric ornithologists such as Richard Meinertzhagen, a ruthless intelligence officer in East Africa, the Middle East and Spain. Meinertzhagen was supposed to have shot his wife one morning with a revolver on their own rifle range but this was never proven. On a more cheerful note Mark Cocker is not unknown to Guardian readers and has his own Country Diary slot.

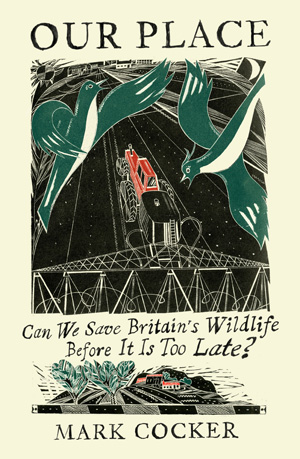

But what of Mark Cocker’s latest book? Our Place – Can we Save Britain’s Wildlife Before it is Too Late? – a radical examination of Britain’s relationship with the land. Mark Cocker is as interested in people as he is in birds and he is not frightened to get his hands dirty digging out old ditches in Norfolk. He dives in the deep end trying to resuscitate five acres of sludgy land near Norwich aptly named Blackwater, half sunken into the ever winding river bed of the Yare. Norfolk: a land of East Enders, East Anglian salt marshes, broads, dykes and washes. A world of reeds, hides and twitchers.

But you would be mistaken if you thought this was a mere nature book, a recitation of duck flights, eels, fishy ways and drainage history. It is in fact a peeling back of the layers of well meaning campaigning and bureaucracy and reserve management. By page six Mark has got into full swing and is questioning why our wildlife is more or less still up a gum tree when so many of us belong to such august tribes and pressure groups as the National Trust and The RSPB. When there are so many competing quangos that harp on about conservation. There are Ramsar sites, SSSI’s AONB’s, SAC’s, SPA’s, Wildlife Trusts, National Parks, Butterfly bodies, even gnats and toads with their own appreciation societies, as well ecology degrees, re-wilding debates, botanical surveys, biodiversity factors, migration coefficients, car park dues and hidden cameras. We all love to belong, to pay our membership dues, to have a voice or at least to feel that we have a voice…

But does it do any good in the end? Environmental thought and politics have become part of mainstream cultural life in Britain. The wish to protect wildlife is now a central goal for our society but where did these ‘green’ ideas come from? To analyse these august bodies and how they evolved and how they have fared is worthy of analysis, even a PhD. But it is only part of the story. Farming has its own unique ability to either destroy or foster wildlife. Farming techniques and political pressure groups, subsidies and supermarket price structures have all had their impact on the landscape. This is a serious debate about our future as a species and one worth following up.

Mark Cocker also looks at six different locations throughout the country and evaluates the state of wildlife in those parts. As varied as the Flow Country of north of Scotland, The Pennines, Derbyshire, Teesdale, nightingales in Kent, South Holland and the delights of mass produced daffodils near Gedney Fen.

Mark is also a devotee of poetry and philosophers, and quotes Henry Thoreau, some time resident of Concord, Massachusetts and John Fowles, sometime resident of Lyme Regis. He uses this quotes from The Tree. “As long as nature is seen as something outside ourselves, frontiered and foreign, separate, it is lost both to us and in us.”

This is a book that looks to the future as well as exploring the past. It asks searching questions like who owns the land and why? And who benefits from green policies? Above all it attempts to solve a puzzle: why do the British seem to love their countryside more than almost any other nation, yet they have come to live amid one of the most denatured landscapes on Earth? Radical, provocative and original, Our Place is a work of environmental history, personal geographical quest and philosophical inquiry.

What Mark says is at times unsettling but he has an insider’s perspective on the front line of conservation. It concerns us all. If you want to hear him speak about the future of wildlife and also find out more about Octavia Hill’s sister Miranda and her ‘Society for the Diffusion of Beauty’ then why not come along to the Electric Palace.