It was the video that clinched it! I’d read the reports of starlings gathering in their thousands at sunset over Chesil Beach but when I saw the video of their murmuration and the liquid patterns they carve in the sky, I knew I had to go to see for myself. So, on the first clear, dry day we set off for West Bexington on the West Dorset coast near where the starlings had been spotted.

West Bexington lies between low coastal hills and Chesil Beach and when we arrived that mid December afternoon, the village felt very quiet. The sun hung low in the pale western sky, its bright yellow disc casting a shimmering, silvery mirror across the water and a warm light across coastal fields. We parked in the beach car park and set off across the shingle, the pea-sized pebbles making for hard going as usual. The sea was calm with just a light swell and waves that barely left a thin white line along the vast sweep of shingle. I had thought there might be more people about to watch the birds but, apart from a few fishermen, their faces turned fixedly towards the sea, we were alone on the beach. The skeletal remnants of beach plants that flourish here in warmer months added to the sense of isolation.

For a short time, we stood by the extensive beds of pale reeds that line the back of the beach. The feathery stems fidgeted and rustled as a light breeze passed and we heard the occasional squawk from birds deep in the reeds but invisible to us. A skein of geese passed eastwards to disappear behind the coastal hills honking loudly as they went and the pale moon appeared above the ridge.

Then we noticed another figure labouring across the shingle, swathed in warm shawls and a woolly hat. She approached us and asked if we had come to watch the starling murmuration. We had of course. She told us that she had seen them perform near here on the two previous afternoons before roosting and this was about the right time. We stood, the three of us now, looking, watching, scanning the sky for perhaps ten minutes, but nothing happened. We discussed the vagaries of watching wildlife and we got colder and colder. The sun, a fiery orange ball by now, approached the horizon and spread its warm glow across the shingle. The moon, nearly full and not to be outdone, rose steadily above the hills.

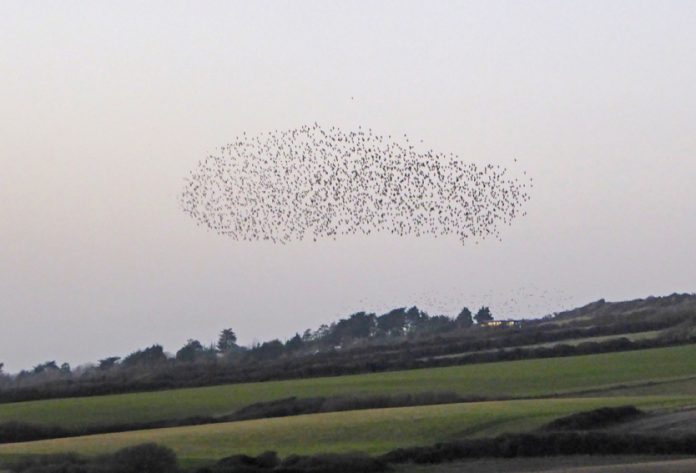

We were on the point of giving up when the first group of starlings appeared in the sky above the coastal hills to the west. At first, they were just a mobile black smudge but soon they began to move about in the pale sky sculpting smooth shapes and occasionally disappearing from view over the dark land. Quite suddenly they were joined by more …… and more……. and more birds, as though some signal had been sent and soon a huge cloud of thousands of birds was moving backwards and forwards forming massive, mobile, liquid shapes that twisted, thickened, thinned and sometimes split apart before merging again. The mass of birds, the murmuration, seemed to have a life of its own, as though it was some kind of sky-bound superorganism squirming about. This was one of the most impressive natural events I have ever experienced, forever engrained in my memory. It lifted our spirits eliciting spontaneous exclamations of surprise and delight.

By now the sun was setting and the light was fading. Suddenly, and without warning, the birds dropped down to roost across the coastal scrub to the west below Othona like a sheet floating to the ground; it was as if another signal had been sent that only the birds understood. With so many starlings, there must have been an impressive noise from their wings when flying and from their chattering when on the ground. I lost all sense of time while the birds were performing their murmuration but when I checked my watch the whole event had lasted only ten minutes and coincided roughly with the setting of the sun.

We marvel at their behaviour but starlings don’t create these pulsating patterns in the sky for our benefit. So, why do they do it? Security is thought to be one reason. Predator birds are always on the lookout for food and as the light fades, individual starlings become more vulnerable. They cannot see the predators well in the fading light but flying as part of large swirling mass of birds provides safety in numbers. Predators find it difficult to focus on single starlings in a moving murmuration so the chance of attack for individual birds will be lower. Starlings are also gregarious and are thought to gather in large numbers as a prelude to roosting close together both to keep warm overnight and to exchange information about good feeding areas. It is tempting after having watched a murmuration to suggest that the birds are also expressing some kind of joy of life.

And yet, starlings are not universally loved. Some people view them as noisy, thuggish and dirty creatures: bird-feeder bullies that soil urban spaces where they roost and have a negative effect on arable farming. Should you take the time to look at a starling, though, you will see a beautiful bird with glossy black plumage enhanced by flashes of iridescent purple or green. Their dark plumage is decorated with startling white spangles in the winter so that, as the poet Mary Oliver says, they have “stars in their black feathers”.

But whether you love them or hate them, starlings in the UK are in trouble. Since the mid-1970s, there has been a 66% drop in their numbers, the starling has been red-listed and is of high conservation concern. The reasons for this decline are poorly understood but are thought to be linked to changes in farming practice. The use of pesticides and synthetic fertilisers and the loss of flower-rich hay meadows have severely reduced numbers of invertebrates such as earthworms and leather jackets that starlings depend on for food. Starlings are dying of starvation and other farmland birds such as tree sparrows, yellowhammers and turtle doves have also been badly affected. Agriculture needs to adjust to make space for wildlife in order to halt this downward spiral before we lose these birds altogether and murmurations become no more than memories.

For some brief videos of this murmuration have a look at my YouTube channel: Philip Strange Science and Nature.