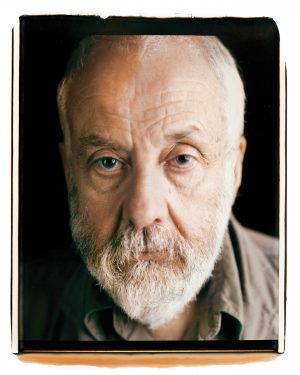

Film director Mike Leigh and composer Andrew Dickson talked to Fergus Byrne ahead of the Mike Leigh Film Festival coming to the Electric Palace in Bridport at the end of February.

For writer and film director Mike Leigh, one of the benefits of the convention of how he makes his films is that, alongside the collaboration of the team he works closely with, he is able to conjure up the finished product through his own imagination. Nothing is determined by outside commercial influences, where, as he puts it, ‘a whole load of producers and people are all interfering and have to check it out.’ The result has been a body of work that is totally unique. From his first feature-length movie, Bleak Moments, in 1971, to this year’s Peterloo—his epic portrayal of the events surrounding the infamous 1819 Peterloo massacre—his films have a unique insignia, a marker that sets them in a league of their own while ensuring the complete individuality of each.

In February, he is coming to Bridport to support a mini Mike Leigh Film Festival at The Electric Palace, which will focus on those films where Bridport’s Andrew Dickson wrote the score. The four-day festival will finish with a showing of Peterloo and will feature a Q&A session with Mike and Andrew each evening. The films to be screened are: Meantime, High Hopes, Naked, Secrets & Lies, All or Nothing and Vera Drake. Although quick to point out that these films are linked only by the composer of the score, he agrees that Andrew Dickson’s work has its own distinctive nature. ‘The scores that he did for my films are quite particular’ he says. ‘The great thing about Andrew is that he is a very idiosyncratic and original musician and composer.’ A talent that fits perfectly with Mike’s way of working. ‘The general convention, in ordinary film making’ he says, ‘is that there is a script kicking around and a composer can read a script before anybody shoots anything and will already have ideas before anything really exists in any proper organic sense. Whereas with my films, there isn’t a script, and having spent a lot of time preparing to do it, we make the film up as we go.’

One of the unique features and challenges for actors that work with Mike Leigh is his insistence that there is no discussion between participants about their parts or their characters until it’s time to begin rehearsals. Even then they will improvise and hone the scenes, rehearsing without full knowledge of the final story. Very often they won’t even meet all of the other actors until the wrap party. He works closely with each actor to develop their character, and a plot gradually emerges. While there is always a film running in his head throughout the process, it is organic and constantly changing and evolving. As he puts it, ‘the film in your head has to be able to grow and expand and contract and develop.’

For the composer, the process is slightly different in that they get sight of a rough cut from which to gather ideas for their score. ‘Even in its roughest form it can be assembled for the composer’ says Mike, ‘so they can start thinking about what they want to do with it. The creative process starts.’ Talking about Andrew, he explains that the most important thing about working with him is that it has to start with Andrew’s emotional response to the film. ‘And that’s why we click because we’re on the same page, the same wavelength, emotionally and in terms of ideas and feelings about life and all the rest of it. Andrew is obviously a purist, as I am. It’s all about working with the material in a completely uninhibited and uninterfered with environment, and arriving at something which is—without being self-indulgent about it—is kind of pure really.’

The process of independent development worked well for Andrew also. The inspiration would come from that first rough cut that he saw. ‘It’s really the overall atmosphere of the film, and the characters’ Andrew explains. ‘Initially, I’d get a few tunes in my head that seemed to fit the atmosphere of the film. I’d play Mike half a dozen different tunes. He might pick one he might pick none. Out of that, I’d develop variations. It’s always a process of eliminating, peeling away—creating an overall theme or feel.’ The tunes themselves were sometimes influenced by work that may have had an earlier incarnation. For example, the opening tune in Vera Drake was one that he had worked on in a band that a then fifteen-year-old PJ Harvey had been in with him. The tune was a song she sang about a goose fair that, as he put it, had the feel of ‘being simple but slightly sinister’. There followed a process of further development which often included rehearsing with whatever band or choir he was working with at the time. Again, in Vera Drake, the professional soprano voices that hint at an eerie memory of lost souls was originally rehearsed by a choir that Andrew worked with in Bridport.

The actual writing of the tunes, however, was the easy bit, according to Andrew. The real work began as the rough cuts came closer to the final film. Getting the timing right was always the hardest. In the days when he wrote those scores, everything was done mechanically, and there were no computer programmes to help tie the music to the film. ‘The way I did it was watching and counting’ he explains. ‘Watching timecode and marking where important pieces of dialogue were. It’s very very precise—in theory to the 25th of a second. Endlessly counting and watching’. For Andrew, the effort was worth it. ‘I loved working with Mike, partly because we became really good friends, but he got stuff out of me that I didn’t know was there. He made me work harder than I’ve ever worked before.’ A comment echoed by many of those that have acted in his films.

There is much fascinating detail about each individual film, from sticking drawing pins onto piano hammers to Mike’s suggestion of playing a tune backwards, that Andrew and Mike will discuss in question and answer sessions at the end of each evening. And there is also no shortage of entertaining, thought-provoking and emotional revelation within the body of work that Mike Leigh has contributed to theatre, television and film over his career—a career that so far spans more than half a century.

From Abigail’s Party to Peterloo Mike Leigh has had an impact on many of our lives and the films being shown at the Electric Palace are a small but powerful selection from his career. The chance to see them and then listen to the director and the composer’s insight is a rare opportunity not to be missed.