As a youngster he was always taught to avoid discussing religion and politics in the pub. So, over a cup of tea, Fergus Byrne talked to John Burton who has written a book making a case for science.

John Burton, a retired medical scientist living in Somerset, makes a striking impression on many levels. His six foot four frame fills the doorway as he welcomes me to his home. Whilst admiring his garden, adorned with what turns out to be his own sculpture, he points out that he doesn’t do much gardening these days – it’s a long way to the ground and bending down isn’t quite as easy as it once was. In his spare time, as well as sculpting he also paints, although his real hobby is book binding. With a very successful career in medical science behind him, three children and assorted grandchildren, as well as a successful writing career, it’s hard not to wonder how he has had time to paint, sculpt and bind books. Harder still to understand where he got the time to write, contribute to, and edit a range of medical textbooks and journals, including a translation of Lazare Riviere’s 17th century book on the diseases of women.

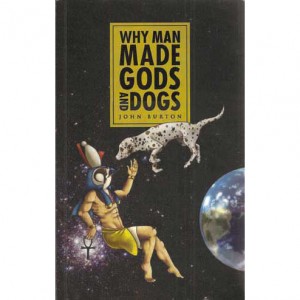

However it is yet another of his literary achievements that has led me to come to meet him. Last year he also found the time to write and publish his first non medical book entitled, Why Man made Gods and Dogs. It is an intriguing, lucid and thought provoking book, providing an overview of modern science as it relates to religion.

Although his life long interest and knowledge of science has naturally led him to question theological thinking over many years, he says that a recent review of science as it relates to religion has led him to the conclusion that man’s belief in God has arisen as a result of evolution of the human brain, and that man made God as a psychological construction here on earth, rather than God having made man as a physical construction some time ago. In his book he tries to give a simple account of the scientific facts that led to this conclusion, as well as including comments from his own personal experiences. The book is laid out as a series of questions that he has tried to answer or at least offer a view on. They cover a range of topics from Multiverse, the theory that there may be many Universes, to the question of whether evolution can produce moral behaviour. He tackles subjects such as physics and spirituality, life on earth, and commonality of religious beliefs across cultures, as well as questions as diverse as ‘Do animals have gods?’ and ‘Who is the Flying Spaghetti Monster?’ A man with a great grasp of the value of humour, he originally conceived the book as a helpful overview of scientific thinking to allow teenagers the opportunity of seeing alternative views. However he admits that the book got a little more advanced and now believes it may well be more relevant to those of university age and beyond.

Based on his background, many might not have expected such high life achievements for John Burton. He explained that neither he nor his pathologist wife Pat had family that had attended university. “We were from that lucky generation of grammar school people” he says. “My father left school at thirteen and he went to work down the coal mine, as did his father. I think his first job was leading pit ponies up and down. He was a bright chap. As soon as he got old enough he left the mining and went to join the army. He was quite big and strong and became a Grenadier Guards boxing champion.” John’s parents impressed on him the need to pass the eleven plus and ‘get on in life’ at a time when the height of ambition would have been to get an apprenticeship at Rolls Royce in Derby. Although initially interested in English and Art it was pointed out to him that without ‘connections’ he could never get a job with an English degree and ‘nobody could make a living with Art!’ He subsequently followed advice to do science because ‘you could get on in science’. And although maths wasn’t his strong point and neither were chemistry and physics, he did like biology. “And then I realised that you could be a doctor” he says. “For previous generations it was actually quite difficult if you’d not got the right family background”. He managed his university years on a maintenance grant and bemoans the fact that grammar schools have since been more or less abolished and the future of free university is in jeopardy. He recalls that there were only two boys that did biology in his sixth form class and both became professors. One became a professor in zoology and John became a professor in dermatology. “And you know both of us were from ordinary homes in pokey little mining towns.” he says. “I don’t think that opportunity exists in the same way now”.

Although Why Man made Gods and Dogs is self published, John Burton’s introduction to writing and publishing was from an era when publishers enjoyed long lunches with potential writers. He remembers how, when he had an idea for a medical text book, he rang Churchill Livingstone in Edinburgh saying “You won’t know me but I’m Dr Burton. I’m a lecturer in medicine and I’d like to write a book for you.” One of the directors took him out to lunch, liked his idea and decided to publish it. As John remembers, “It sold like hot cakes, went into six editions and was translated into many languages.” As a result he was able to buy a car. “Prior to that I was on a bicycle” he says. “I was able to buy a Citroen Dianne on the royalties.”

Times have moved on and John has no expectations of buying a new car on the royalties from his latest book. As the son of a devout Christian mother and an atheist father I was interested in what initially sparked his decision to write the book. He explained that, as two of his children had each married a partner with a strongly religious mother, he felt uncomfortable with the fire and brimstone doctrine that held that his grandchildren had God always watching them, and that they should live in fear of going to hell if they didn’t conform to religious dictates. “I didn’t really entirely agree with this” he says. “And I thought it’s only right that these kids should, as they grow up, learn the other side of the story and learn some science at the same time. So this was an attempt originally to be aimed at teenagers who I hoped would start to think for themselves. It was an effort to update them about modern science and to teach them you can think about things without going to hell, and that you can still be a moral person. Then the more I thought about this I thought, why is it that Richard Dawkins and the Archbishop of Canterbury could never agree? The evidence is the same, they’re both educated well meaning people – how is it they just can’t seem to agree? And then I began to think that it’s quite likely that humans, as they evolved from the apes and got intelligent enough to ask scientific questions which they couldn’t answer, would have to impute some supernatural power, which in other words is a sort of god. And over the thousands of years obviously there have been many different gods, the ancient Greeks, the Egyptians, the Romans and there’s still thousands of different religions, and they can’t all be right. It’s obvious they can’t all be right. And it’s purely a question of this need for a father figure and an afterlife and an explanation of things we don’t understand. And which particular god you choose is what you’re taught by your particular culture. It’s usually your parents but it could be your school or your friends and so on.”

John’s other motivation was also grounded in the realities of modern living. He was concerned about how some religious interpretation can inflame hatred and violence. He says “The Koran does inflame a lot of these young suicide bombers and they do believe in paradise and the virgins.” He feels that if young people were given the opportunity to question their regimented indoctrination they may not blindly follow teachings that lead to needless destruction of lives.

He doesn’t hold out much hope that elderly religious people will be influenced by his book in any way and has found many friends and neighbours happy to engage in friendly debate. He even agreed to a debate with the local vicar in his village hall. “Loads of people came” he says. “And both of us were very happy with the outcome. It was a very civilised debate and the audience all joined in, there were humanists and devout religious people and they all made their point in a very nice, pleasant way without shouting at each other. I’ve got nothing against the benign Church of England who, by and large, do nothing but good. What is practised around this area is totally admirable.”

In the introduction to Why Man made Gods and Dogs John Burton points out that, although an atheist for many years, he once attended an Alpha course organised by the Church of England and there met two religious people that surprised him and gave him pause for thought. One was a Professor of Biochemistry who believed that the technical difficulties are so great that only a supernatural God could have created living cells from inanimate chemicals. The second, a physicist, had become more and more spiritually inclined as he learnt the complexity of the mathematical and physical laws which govern the universe. He had come to believe that a supreme intelligence must have set up and organised the immutable Laws of Physics, so that the Universe could develop and life could form. Following this introduction, John goes on to produce powerful scientific arguments and present a case for atheism. However, as he told me before I left him at his home in the gentle Somerset countryside, “When it comes down to it people will still say ‘Well it’s all very well what you say John, but I still think there’s something…’” And as he admits himself “I can’t argue with that.”

Why Man made Gods and Dogs, ISBN 978-0-9565588-0-0 is published by Perrott Press and copies can be ordered from perrottpress@hotmail.com. Any profits from the sale of the book will be donated to the National Eczema Society.