Blizzards, strong winds, drifting snow, bitter cold – that was the story in early March last year when the “Beast from the East” collided with storm Emma bringing extreme weather and disruption to life across large parts of the UK. Towards the end of June, by contrast, the sun began to shine and daytime temperatures climbed into the thirties and stayed that way across much of the country until August. Elsewhere across the globe, reports came in of flooding, wildfires, severe tropical storms and unusually high and low temperatures. Many of these weather extremes can be attributed to climate change and there is considerable concern that the planet is heading for climate catastrophe. David Attenborough expressed this fear at a climate change conference in Poland: “If we don’t take action, the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon.”

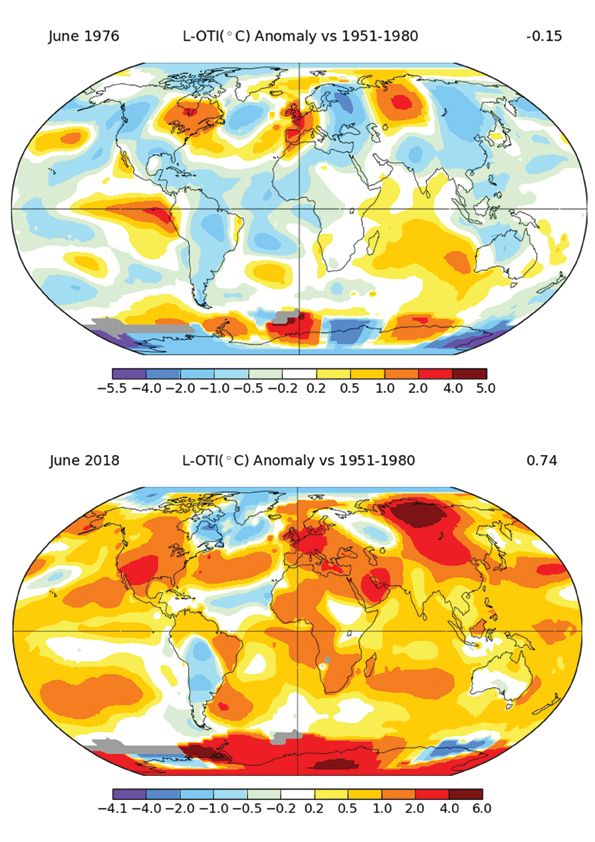

In the UK, it was the long, hot summer, the joint hottest on record, that made people think most about a changing climate. The weather here is, of course, notoriously fickle and some will remember that in 1976, we experienced a similar long, hot, dry summer, so how can we disentangle normal weather variation from climate change? One way of looking at this was shown by Simon Lee, a PhD student at the University of Reading, who shared graphs on Twitter of the global temperature anomalies in June 1976 and in June 2018 (see pictures). These show that in 1976 the UK was one of a few unusually hot spots in an otherwise cooler than average world whereas in 2018 much of the world, including the UK, was hotter than the average. The 2018 picture shows climate change in action: the planet is warmer making heatwaves more likely.

Careful measurements of the average surface temperature of the planet show that it is currently about 1°C hotter than in pre-industrial times. This may not seem very much but it is enough to disturb the complex systems that create our weather. As a result, heatwaves may be more frequent. in summer and, in winter, polar air may be directed southwards bringing abnormal, freezing temperatures. Also, a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture so that rain and snow may be more severe. Climate breakdown might be an apt description of these changes.

This global heating is a result of human activity. The emission of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels such as coal, gas, oil and petrol, traps heat in the atmosphere so the temperature of the world increases. We have known this for some time and we have also known that the solution is to reduce carbon emissions. Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide have, however, continued to climb because no government has had the will to introduce the extreme lifestyle changes required to curb emissions. Some governments, including our own, have even encouraged the continuing extraction of fossil fuels.

It is, therefore, significant that in October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a report containing a dire warning: we must make urgent and unprecedented changes to the way we live if we are to limit heating to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels. To achieve this target, we must reduce net global carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 and to zero by 2050 – fossil fuel use must be drastically reduced by the middle of the 21st century but we must start the reduction now. Should we fail to achieve this 1.5oC target, the risks of drought, flooding, extreme heat, poverty and displacement of people leading to wars will increase significantly. The world will no longer be the place we know and love and parts of it will become uninhabitable for humans and the rest of nature.

How do we achieve this reduction in carbon emissions? Voluntary measures such as suggesting people fly or drive less will not work. The only way this reduction can be achieved is through coordinated government action based on recommendations made in the IPCC report. These include the planting of more forests and the chemical capture of carbon dioxide to reduce atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide. There must also be a drastic shift in energy production and in transport away from fossil fuels and this can be driven in part by investment and subsidies directed towards clean technologies. A carbon tax can also help drive this shift but the tax will need to be high enough to force change, for example by taxing energy companies who burn fossil fuels so that they invest in cleaner technologies. In the short term, costs to consumers may rise, so politicians would need to keep the public on side, for example, through tax incentives. If we grasp the opportunity, the scale of change may have the unexpected bonus of allowing us to design more sustainable and equitable societies.

The IPCC report set out very clearly the changes required to avoid damaging global climate change so there was great anticipation when the UN Climate Change Conference convened in Katowice in Poland just before Christmas. Astonishingly, given the gravity of the situation, the 200 countries represented there failed to agree new ambitious targets for greater reductions in carbon emissions. Four countries (USA, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Kuwait) would not even sign a document welcoming the IPCC report; these countries are of course all oil producers.

It was at this conference that David Attenborough issued his warning about the collapse of civilisations but there was another hugely impressive intervention. This came from 15-year old activist Greta Thunberg from Sweden. She had already achieved some notoriety through her weekly climate strikes where she missed one day of school to protest about climate change. Her actions have stimulated many thousands of young people around the world to do likewise. Thunberg also spoke in London at the launch of the new grass-roots movement, Extinction Rebellion, which intends to use peaceful protest to force governments to protect the climate. These new trends offer some hope for the future since it is the young of today that will bear the climate of tomorrow.

Here is part of Greta Thunberg’s speech given at the Katowice conference:

“For 25 years countless people have come to the UN climate conferences begging our world leaders to stop emissions and clearly that has not worked as emissions are continuing to rise. So, I will not beg the world leaders to care for our future, I will instead let them know change is coming whether they like it or not.”

“Since our leaders are behaving like children, we will have to take the responsibility they should have taken long ago. We have to understand what the older generation has dealt to us, what mess they have created that we have to clean up and live with. We have to make our voices heard.”

Philip Strange is Emeritus Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Reading. He writes about science and about nature with a particular focus on how science fits in to society. His work may be read at http://philipstrange.wordpress.com/