‘I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my mother Peggy Hurst who told me much about my family and even after his death talked so much about my father Gordon. Although I remember Gordon as a person in my very young life, I was alas too young to really know him and to be able to recognise and then to value his wonderful qualities. Peggy had met him while training to be a nurse at University College Hospital in Gower Street, London. He was one of her patients. When they started to go out together to concerts and plays and walks in London parks, this was pretty daring – nurses were not supposed to form relationships with their patients. They married and Gordon practised law and they went on honeymoon to Switzerland. Not long after I was born we embarked on World War II and life became quite difficult. I remember watching doodlebugs – flying bombs – flying overhead and huge waves of bombers filled the sky. I remember the sound of air raid warnings and the all-clear – in fact, the sound is quite vivid even now. I remember the Anderson shelter – a big bunker in the garden. The Morrison Shelter was really our dining table with a steel sheet on top which we all used to sleep under at night in case the Germans dropped a bomb. One night a bomb dropped nearby and blew our French doors into the garden and there was glass everywhere. I was too young to be frightened.

I remember Lyme Regis best of all – my grandparents’ home. Hole Cottage was paradise and where I spent most of my childhood because it was safer to be down there. Sometimes Peggy and Gordon were able to be there too. I played in the fields and helped on the farm down the road. I remember haymaking with horses and carts with the Hallets. I remember the rabbits running out in front of the scythes and the cart. The horses were huge shire horses. I remember the American soldiers who were all over Dorset as they prepared for D Day. They had jeeps and used to give me chocolate.

My grandfather (Grampy) kept chickens which ran wild everywhere and I was once attacked by the cockerel which frightened me. Hole Cottage was the former gamekeeper’s cottage on the Woodroffe estate. Old man Woodroffe was very good to Granny and Grampy. Hole Cottage was very primitive – no electricity or running water. Water came from a well in the garden and I can remember the excitement when a tap was installed in the wood – but we still had to carry the pails into the house. The loo was the Ivy House in the garden. The place was always full of creepy crawlies and I didn’t like staying there very long. I used to have a bath in an old hip bath in front of the fire in the drawing-room. Every evening oil lamps were lit and we went to bed early, the whole house creaked and I was often frightened in the dark. Aunt Nancy said she once saw a ghost at the cottage – a man hanging from a beam in the barn. Apparently a man did hang himself there in years gone by but she had a vivid imagination and she may not have seen it. I never did, fortunately! Every evening a lovely white barn owl would come swooping down the drive as regular as clockwork and roost in the barn.

I was once accused by Granny of telling a fib about something. I immediately dived under the dining table and said, “God, aren’t I telling the truth?” Then in a deep voice, I replied “Of course you are telling the truth Anthony”. Resurfacing I said, “There you are.” Everyone assumed that odd expression when trying to look serious but wanting to laugh. It was a really idyllic childhood and my heart will always be in Lyme. I was totally safe and free from danger. Everyone was kind to children, no-one put pesticides in fields and everything was green and sunny.

Of course, there was a world war going on and countless people were suffering terribly but I was too young to know all this. I remember long train journeys in the blackout when the train would stop for hours in the middle of nowhere while an air raid was going on. I clearly remember going up to London with Peggy at the end of the war and standing in the crowds and her looking down at me saying “Isn’t it wonderful Anthony, the war is over”.

At about this time we went to Bournemouth as Gordon was now very ill and in a sanatorium there. To be near him Peggy got a job as a matron in a private school and I became a pupil there. One day Peggy took me by bus to the cliffs overlooking Bournemouth and told me “Daddy has gone to live with Jesus. He has got a special job for Daddy to do because he was a special person.” Vivid now as it was then, I think it was a lovely way to explain my father’s death to me and I didn’t need any more.

Being ill, Gordon had had no chance to establish himself in his profession so there was very little money. Despite being unable to type, Peggy got a job as PA to the manager of Croydon airport which used to be London’s major airport. She then set about writing over a hundred letters to find a Governor who would send me to Christs Hospital, an independent school in West Sussex. She didn’t give up and was eventually successful. In January 1948 at the age of nine I entered the prep school of Christs Hospital. It was and has always been an outstanding school founded by King Edward VI for the sons (and now daughters) of families who are in need. Though wonderful as ‘Housey’ is, it was a pretty daunting place for a nine-year-old, especially one lacking in confidence like me. I can remember the food which was generally revolting and in short supply. We used to buy slices of bread and butter to keep body and soul together. My major pastime was roller-skating which I became quite good at and played many games of roller skate hockey. My time at ‘Housey’ was totally undistinguished. I was neither good at work nor a brilliant frames player and generally felt rather insecure. I played cricket, my best game and rugger for my house but was never good enough for school teams.

Peggy had started a new phase of becoming a sort of universal aunt – going to look after families where the mother had had to go to hospital for some reason. It provided money and gave us a stable base. We moved to Lyme Regis where Peggy became matron at Rhode Hill which was then a girl’s domestic science college and finishing school. We lived in the lodge and it was really like having our own home. I loved it there.

Careers advice was pretty rudimentary in those days. Peggy told me that, concerned at my lack of scholastic ability, she had gone to ask what I was likely to do after school. There was much sucking of teeth and drawing of breath and she was eventually told: “Well I think Anthony should concentrate on just being a nice chap.” At about this time I injured my knee playing rugger and had to have my whole leg in plaster for six months. It didn’t seem to be making progress so Peggy took me to a specialist in Harley Street who also professed to be a faith healer. He took me into a room where we knelt down and said a couple of prayers. All I can say is from that day on I have never felt any pain and I did start playing rugger again. Furthermore, it withstood the rigours of an Infantryman’s life without any problems. Uncanny but true.

Nevertheless, it rather spoiled my plans to be a soldier because all the surgeons told me that my knee would never be strong enough for the army. I got a job with BP but hated it and still hoped to be a soldier. So I reckoned the thing to do was join through National Service where I thought the medical might be less stringent. I didn’t mention the leg and they didn’t find anything wrong. So in August 1958, I went to join Salamanca Platoon at the Regimental Depot of the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment at Topsham Barracks in Exeter.

Basic training was not very remarkable. After ‘Housey’ and the CCF, it was not too difficult at all, but some people had a real problem with it. I was astounded to discover that some twenty-year-olds had never made their own bed or cleaned shoes before. Some could barely read and write. By this time I was too old to go to Sandhurst. I went to Mons Officer Cadet School at Aldershot and received the Queen’s Commission in December 1958. I then embarked on the SS Devonshire at Southampton – a fine old troopship. We had the 9/12th Royal Lancers on board and it was really one long party. We went ashore at Gibraltar and Malta and finally docked at Famagusta at dawn one morning. I commanded 9 Platoon and we patrolled looking for EOKA, a nationalist guerrilla organisation fighting a campaign for the end of British rule in Cyprus, but things were beginning to quieten down and there were no contacts. During this time I had a letter from Peggy who had decided to marry a man named Ted Honore and was going to live in Kenya. I took compassionate leave to help her pack up the house and saw her onto the ship at Tilbury before returning to Cyprus.

We led a very social life, dressed for dinner each evening in the mess, cocktail parties and curry lunches on Sundays and invitations to supper with various married officers. When I was ‘dined in’ to the regiment I had to drink a Regimental cocktail of Advocaat, Crème de Menthe and Cherry Brandy which sat in layers in the glass. After dinner, I had to return to my tent halfway up a mountain in the back of a Landrover and I don’t think I ever felt worse!

On one occasion we had to guard an explosives store at a copper mine at Agasta up in the Troodos. Cooking our tea, one L/Cpl McFie tried to fill the burners with petrol while they were still hot and there was a mighty explosion which sent him flying through the air towards my tent. He was unhurt but the following fire spread rapidly and completely demolished the cookhouse, all our weapons and radios and the ammo. Pretty soon the ammo caught alight and it became like the Fourth of July. My worry was that it might spread to the explosives store which thankfully it didn’t. The next morning, fully six hours after the fire had burnt itself out, the Cyprus Fire Brigade arrived. As the one in charge, I carried the can for the thousands of pounds of British taxpayers’ money that had gone up in smoke. I was lucky to get away with a caution. On another occasion, learning to drive I struggled coordinating hand signal, gear change and steering wheel all at the same time and ploughed straight through a plate glass window into a barbershop. I went back there many years later and the barber shop was still there but had been renamed ‘Reflections of London Salon’.

I then had a spell in Lybia where you could fry eggs on the bonnet of a Landrover. The most memorable event was the earthquake at Barce. A small group of us were the first on the scene to help. We were all in our twenties except for some of my NCOs and we grew up very quickly that night. We all saw things that we hoped never to see again. The locals would call us shouting “bambino, bambino” pointing to a pile of earth. Naturally, we dug furiously and sometimes we did find the bodies of little children but often it was a ruse by the locals to get us to dig up their goods and chattels. By dawn, though, we had collected a large pile of bodies and rescued some injured. The process of clearing up went on for many days. It was an event that made a deep impression on us and I was certainly never to forget that night.

Afterwards, I took some leave to visit my mother and Ted in Kenya. I left my trunk in the care of the night watchman and have never seen it since. Back in the UK, my daughter Karin was born to my first wife Bunty. I had a brief posting to Belfast during the troubles, then on to train recruits in Honiton while Topsham barracks was being rebuilt. There were other postings including Germany and during this period my son Robin was born.

Then it was off to Singapore for three months to learn Malay followed by three months in Hong Kong via Vietnam. Then back to Malaya and jungle warfare training at Khitai Tinnghi just to the north of Johore Bahru. The jungle was wet, hot, noisy and vaguely threatening, I never really felt at home in it. Snakes everywhere and leeches which are revolting. They attach themselves to you as you move through the ‘ulu’ and start off the size of the end of a bootlace but soon become the size of your thumb. I learnt how to survive on what could be found to eat in the jungle and how to recognise what was poisonous. I learnt all about patrolling in the jungle, the rudiments of tracking and how to lay an ambush. We were up against Korp Kommando Operasi – Indonesian Marines and some of their better troops who were tough and well-trained. Patrolling in the jungle was uncomfortable; frequent stops to check for leeches and to check where the hell you were; clinging vines, snakes, creepy crawlies and beautiful huge butterflies. Thigh deep in revolting mangrove swamps then stopping before dark to build a basha for the night – a bed of bracken or groundsheet on sticks covered loosely with another groundsheet. When you returned from ten days of this the smell was unbelievably awful to everyone else. Standing naked in a monsoon to get clean was very simple. The worst thing was being closed in. You never knew what was behind the nearest bush and one operated on a constant state of alert and adrenaline.

At thirty-one I decided to leave the army. It remains the most seminal period of my life. I didn’t achieve anything dramatic but felt I’d done better than most people would have predicted in my school days.

Civilian life began with a job at Unilever in personnel management which was the start of a difficult period. My marriage failed and I worried about the children. Part of my role was to handle industrial relations negotiating with seven different Trade Unions. I quickly realised that almost all problems were not the fault of a bolshy workforce but due to weak and incompetent management. I learned a lot in having to defend my corner against some very tough and powerful people. In some ways, Unilever was like the army – both very large bureaucratic organisations. But the people were not soulmates really. I was part of a small team and missed my “soldiers”. During this time I lived in Sevenoaks and was married to Melita.

This was followed by a stint working for the County of Avon based in Bristol. It was my first experience of politicians and the political process. It is very unsavoury. When politicians use words like trust and loyalty they are not using them in the sense that I know. I learnt soon enough that I couldn’t trust any of them. During this time I remarried again to Carole and my son Robin left home to make his way in Bath while my daughter Karin went to live in Cheltenham and start secretarial college. My job didn’t improve and it was definitely my least enjoyable working experience, my worst ever boss and zero satisfaction. It was also a time of my highest ever salary and the happiest and most fulfilling time in my private life. Well, you can’t have it all – not at once anyway.

The next period of my working life was mostly taken up as a consultant. I had very wide-ranging experience having managed people and events since the age of twenty in a huge variety of organisations and circumstances. I worked for a company and found myself running courses in masses of things – leadership, motivation, team-building, negotiation, presentation skills, time management, communication and so on. Sadly Carole went back to Canada; so a very sad personal period coinciding with a rather fun, satisfying job.

A job I really enjoyed never coincided with a happy personal life and vice versa. How odd.

In time I set up as an independent consultant. I loved this work with clients as diverse as Westlands and a small Nursing Home in Seaton. I worked for pretty well every size and type of company in between.

I am aware that I probably view my soldiering days bathed in a rosy glow. Of course, it wasn’t all good. But I would say that the general standard of performance was much higher than I found in Civvy Street. Of course, there were lazy and incompetent people in the army, but they were quickly identified and they sure as hell were not promoted.

My private life was often difficult. I had only had two role models – one was Peggy’s descriptions of life with Gordon, which as far as I know was one of those marriages made in heaven. I never saw adults disagreeing with each other in a serious way and for some time didn’t understand that good relationships don’t just happen. I rather thought that you fell in love and everything was alright after that and you lived happily ever after. That was a hopeless preparation for life and looking back I am horrified at my naiveté and lack of understanding. Considering the difficulties they had to contend with I am lucky to have such normal and wonderful children. I love them both very much and now my grandchildren too.

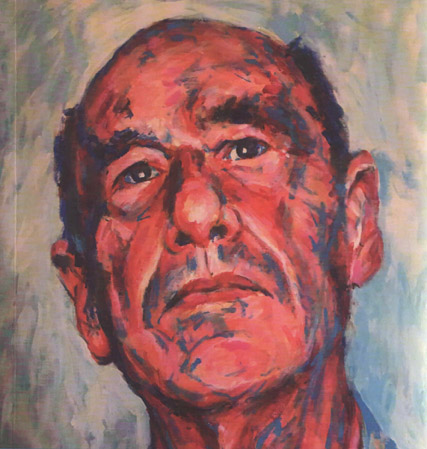

Occupying my time has never been difficult and I am seldom bored. My great joy is painting which I have treated like work in the sense of taking every opportunity to learn and put in the hours of work. I took part in Dorset Art Weeks in 2006 and was staggered to find that 418 people traipsed through my garage to my studio. I like nothing better than to use my painting to make money for the Army Benevolent Fund and the Not Forgotten Association.

I have been extraordinarily lucky to have a wonderfully loving and supportive mother who was a rock for two more generations and loved being both a grandmother and great grandmother. I have also had a wonderful network of supportive friends including my most recent drinking buddies from The Tiger in Bridport who joined me on memorable cruises on the Thomson Celebration and the Norwegian Epic.

Well, it is 2020 now and in December I shall be 82, which is a startling thought. I have lost too much weight – now only 6 1/2 stone. This is rather frightening but my GP is helping me to put some weight on. In any event, I won’t give up and intend to go on living my life to the full. I will not give up without a fight. I continue to love and enjoy my family and friends and know how lucky I am. I will continue to perform random acts of kindness and try to make my little bit of the world a better place.’