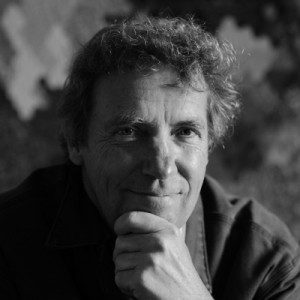

Robin Mills went to Bridport to meet Alan Heeks. This is his story.

“I was actually born in Bournemouth, which was Hampshire in those days, but my mother’s side of the family was very West Dorset. Grandfather was called Robert Wakeley, and he came from Loders, and then moved to Bournemouth. Mother’s mother was a Dashwood, from Piddletrenthide. So having finally moved to West Dorset only a couple of years ago, it’s been like coming home because this is definitely where my roots are.

At school I loved English Literature, and went on to university at Oxford to study it. At university I’d enjoyed promoting functions like exhibitions and theatrical events, so when I’d finished I decided I’d go into marketing, and got a graduate trainee job with Procter and Gamble. I went straight into work, no gap year, from Oxford to work in Newcastle upon Tyne, and I still have mixed feelings about that move. It was quite a shock, going from a free-and-easy Oxford student life immersed in literature and philosophy to a hard-nosed, structured business world. The company operated like a machine, which from the word go raised the question with me about how to bring about human fulfilment in work, and still make a business profitable. In a sense that was quite a fruitful shock for me, because that was a question that has stayed with me ever since, and once I become passionate about something, I stay with it. That marketing job was also hugely beneficial, in that I have been able to apply the same methodology to non-profit ventures I’ve undertaken in later life.

I spent four years with Procter and Gamble, and although I progressed in the company, it was clear the work wasn’t for me. I’d met my wife in Oxford, married in Newcastle, so I took the gap year then, and we travelled in Africa and Asia. Then I got a scholarship to go to America and study for an MBA at Harvard, where there was research into human fulfilment within working life. When I came back from the States, I got a job in Merseyside, as marketing manager of Hygena Kitchens; then I became a founder member of a group called Caradon, and worked as the managing director of the largest subsidiary, Twyfords Bathrooms. During the four years I was there as MD I was able to put into practice some of my ideas about improving human fulfilment, as well as the business results. One of my favourite films is the Ealing comedy I’m All Right Jack, and this company was straight out of the film. There were five dining rooms, each for different levels of staff within the company from the directors down to the ‘peasants’, and basically the workers had never seen, or met, the management. So I introduced a single canteen where everyone ate, and regular meetings between management and staff in which eventually all 1600 staff got to meet and talk to everyone in management, and once it was clear we were genuine, everyone went along with it, results improved, and more importantly morale improved as well.

After four years, I was ready for a major change. I was 40, had been working incredibly hard, and was missing out on family life; I was worried about what sort of life I was bringing my kids into. So, I gave back the Jaguar XJ6, gave up the big office and full-time secretary, and set myself up as a management consultant and trainer. However, as well as the consultancy work, since 1990 I’ve been involved with creating non-profit ventures. The thread of these has been what could be called land based sustainable education, using some sort of project which gets people into closer contact with nature, with two aims; to bring about not only better understanding of environmental sustainability, but also human sustainability. I firmly believe that the same principles apply to both; I think many people are being factory farmed in their working life, in the same way that the natural environment is.

When I left my business career behind in 1990, I already had a vision of these ideas; meeting some visionary and like-minded Dorset people, like Mark Measures, and Will Best, helped me put things into practice quite quickly. I never had any doubts about establishing this project in Dorset, because there do seem to be more inspiring and innovative people here, and pioneering centres like Pilsdon, Monkton Wyld and Othona have suceeded. We formed a charity and bought a run-down 130 acre beef farm on the Somerset/Dorset border, called Magdalen Farm, with a courtyard of buildings that lent themselves to conversion into a residential centre.

In one sense it was a crazy idea for me; I had no background in farming, running a charity, or education, but I had the time and the commitment. Also, the Harvard training does teach you to be a business paratrooper, to land in unknown territory and find the right people to provide the expertise. Over the first few years we learned as we went, and experimented a lot. We converted the farm to organic, evolved curriculum-based education for school children in a residential setting, with added personal and social education—things like trust games, night walks, learning about food and farming, the differences between organic and conventional. The Magdalen Project is still going strong, 21 years later.

From the experience of creating the Magdalen Project, I realised that organic farming was actually the model I had been looking for in my search for human fulfilment within the workplace, so I started to run business training workshops at the farm, using organic farming techniques as examples of sustainable production which people could apply their own businesses. In 2000 my first book was published, The Natural Advantage: Renewing Yourself, which I wrote both for individuals and business organisations.

I had been thinking a lot about what I call the next level of sustainability. There is a limit to how much energy consumption we can reduce in our homes with technical solutions like double glazing and insulation in our lofts. Food and travel accounts for more than half the average household’s energy consumption, and whilst I was interested in sustainable building, I was also concerned with human sustainability in a community sense; my marriage had by now broken up and I was living on my own. In about 2002, I found out about cohousing, a well-established concept in Scandinavia, although quite new here. It’s based on small self-contained dwellings, so everyone has their own front door and their own space, but there are shared facilities like a garden courtyard where people can easily meet and chat. There is also a common house, a bit like a village hall, in which there can be shared meals, parties, meetings, film shows, etc.

It can meet the needs of people who are very sociable as well as those who aren’t, unlike a commune. I formed a group of interested people, and in 2004, the project came about in North Dorset, called the Threshold Centre, near Gillingham. It’s the first project of its kind in the UK done in cooperation with a housing association, so half of the properties are affordable, and it’s successfully demonstrating ideas of lifestyle sustainability, with its own one acre community garden growing food for the householders, and a pool car and ride-sharing. I’m also very proud of the fact that the ecological footprint per household has been measured at half the UK average, despite its rural situation and poor public transport service. There are 14 households, with young families, older people, and a wide range of social backgrounds.

I always intended this to be a stepping stone for a bigger project, one in West Dorset, so in 2009 I began to look for local people to put together something similar in Bridport. By now we have 24 members, and we are working with the same Housing Association as at Gillingham who will act as the developer, so that at least 40% of the properties will be affordable to people on the Housing Register. The District Council is now open to innovative forms of affordable housing, and we’re hoping to submit a planning application within the next year for 30 dwellings, which means that we’re still looking for more members to join.

One of the things I’ve been involved with over the last 15 years or so has been men’s groups, and this relates to the second book I’m writing. When my marriage broke up, the best support I had came from a men’s group. I’m particularly interested in men over 50, who these days, possibly up to age 80, often have quite good health, have more time, enough money, and opportunity, but can suffer from loneliness, depression and addictions, because they need the life skills to deal with the ‘shipwrecks’ that often occur at this time. So I’ve set up a website and a blog to help men in this situation, and I’m working with a retired GP from Maiden Newton, Max Mackay-James, to offer resources to men in this age group. Perhaps men aren’t good at collaborating; it’s been said that men get to know each other shoulder to shoulder, not face to face.”